Social robots as language learning companions for children

Language learning is, by nature, a social, interactive, interpersonal, activity. Children learn language not only by listening, but through active communication with a social actor. Social interaction is critical for language learning.

Thus, if we want to build technology to support young language learners, one intriguing direction is to use robots. Robots can be designed to use the same kinds of social, interactive behaviors that humans use—their physical presence and embodiment give them a leg up in social, interpersonal tasks compared to virtual agents or simple apps and games. They combine the adaptability, customizability, and scalability of technology with the embodied, situated world in which we operate.

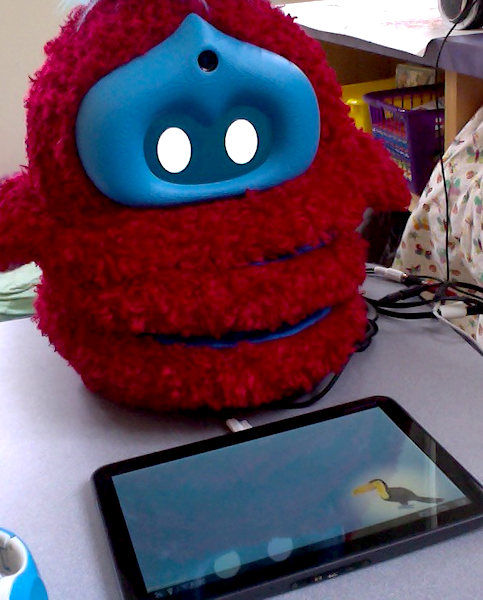

The robot we used in these projects is called the DragonBot. Designed and built in the Personal Robots Group, it's a squash-and-stretch robot specifically designed to be an expressive, friendly creature. An Android phone displays an animated face and runs control software. The phone's sensors can be used to capture audio and video, which we can stream to another computer so a teleoperator can figure out what the robot should do next, or, in other projects, as input for various behavior modules, such as speech entrainment or affect recognition. We can stream live human speech, with the pitch shifted up to sound more child-like, to play on the robot, or playback recorded audio files.

Here is a video showing the original DragonBot robot, with a brief rundown of its cool features.

Social robots as informants

This was one of the very first projects I worked on at MIT! Funded by an NSF cyberlearning grant, the goal of this study and the studies following were to explore several questions regarding preschool

children's word learning from social robots, namely:

- What can make a robot an effective language learning companion?

- What design features of the robots positively impact children's learning and attitudes?

In this study, we wanted to explore how different nonverbal social behaviors impacted children's perceptions of the robot as an informant and social companion.

We set up two robots. One was contingently responsive to the child—e.g., it would look at the child when the child spoke, it might nod and smile at the right times. The other robot was not contingent—it might be looking somewhere over there while the child was speaking, and while it was just as expressive, the timing of its nodding and smiling had nothing to do with what the child was doing.

For this study, the robots were both teleoperated by humans. I was one of the teleoperators—it was like controlling a robotic muppet!

Each child who participated in the study got to talk with both robots at the same time. The robots presented some facts about unusual animals (i.e., opportunities for the child to learn). We did some assessments and activities designed to give us insight into how the child thought about the robots and how willing they might be to learn new information from each robot—i.e., did the contingency of the robot's nonverbal behavior affect whether kids would treat the robots as equally reliable informants?

We found that children treated both robots as interlocutors and as informants from whom they could seek information. However, children were especially attentive and receptive to whichever robot displayed the greater nonverbal contingency. This selective information seeking is consistent with other recent research showing that children are, first, quite sensitive to their interlocutor's nonverbal signals, and use those signals as cues when determining which informants they question or endorse.

In sum: This study provided evidence that children show sensitivity to a robot's nonverbal social cues, like they are with humans, and they will use this information when deciding if a robot is a credible informant, as they do with humans.

Links

Publications

-

Breazeal, C., Harris, P., DeSteno, D., Kory, J., Dickens, L., & Jeong, S. (2016). Young children treat robots as informants. Topics in Cognitive Science, pp. 1-11. [PDF]

-

Kory, J., Jeong, S., & Breazeal, C. L. (2013). Robotic learning companions for early language development. In J. Epps, F. Chen, S. Oviatt, & K. Mase (Eds.), Proceedings of the 15th ACM on International conference on multimodal interaction, (pp. 71-72). ACM: New York, NY. [on ACM]

Word learning with social robots

We did two studies specifically looking at children's rapid learning of new words. Would kids learn words with a robot as well as they do from a human? Would they attend to the robot's nonverbal social cues, like they do with humans?

Study 1: Simple word learning

This study was pretty straightforward: Children looked at pictures of unfamiliar animals with a woman, with a tablet, and with a social robot. The interlocutor provided the names of the new animals—new words for the kids to learn. In this simple word-learning task, children learned new words equally well from all three interlocutors. We also found that children appraised the robot as an active, social partner.

In sum: This study provided evidence that children will learn from social robots, and will think of them as social partners. Great!

With that baseline in place, we compared preschoolers' learning of new words from a human and

from a social robot in a somewhat more complex learning task...

Study 2: Slightly less simple word learning

When learning from human partners, children pay attention to nonverbal signals, such as gaze and bodily orientation, to figure out what a person is looking at and why. They may follow gaze to determine what object or event triggered another's emotion, or to learn about the goal of another's ongoing action. They also follow gaze in language learning, using the speaker's gaze to figure out what new objects are being referred to or named.

Would kids do that with robots, too?

Children viewed two images of unfamiliar animals at once, and their interlocutor (human or robot) named one of the animals. Children needed to monitor the interlocutor's non-verbal cues (gaze and bodily orientation) to determine which picture was being referred to.

We added one more condition. How "big" of actions might the interlocutor need to do for the child to figure out what picture was being referred to? Half the children saw the images close together, so the interlocutor's cues were similar regardless of which animal was being attended to and named. The other half saw the images farther apart, which meant the interlocutor's cues were "bigger" and more distinct.

As you might expect, when the images were presented close together, children subsequently identified the correct animals at chance level with both interlocutors. So ... the nonverbal cues weren't distinct enough.

When the images were presented further apart, children identified the correct animals at better than chance level from both interlocutors. Now it was easier to see where the interlocutor was looking!

Children learned equally well from the robot and the human. Thus, this study provided evidence that children will attend to a social robot's nonverbal cues during word learning as a cue to linguistic reference, as they do with people.

Links

Publications

-

Kory-Westlund, J., Dickens, L., Jeong, S., Harris, P., DeSteno, D., & Breazeal, C. (2015). A Comparison of children learning from robots, tablets, and people. In Proceedings of New Friends: The 1st International Conference on Social Robots in Therapy and Education. [talk] [PDF]

-

Kory-Westlund., J. M., Dickens, L., Jeong, S., Harris, P. L., DeSteno, D., & Breazeal, C. L. (2017). Children use non-verbal cues to learn new words from robots as well as people. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction. [PDF]