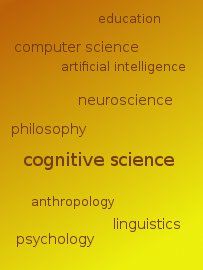

Why did you pick cog sci?

When I can tell a ten-second answer is all that's wanted, I say, "because I took an intro cognitive science class in my first semester of college and loved it."

Some people realize I must've had some reason for signing up for an intro cog sci class in the first place. They tend to be satisfied with an answer like "because I read a book on consciousness before college, and wanted to know more."

The real answer, the one that's actually about why, is this:

No one knows yet how or why I'm a self-aware person. And I'd really, really like to find out.

Mysteries and mysteries

A couple years before I ventured across the country to begin my Vassar education, I started reading books about mysteries. Not fiction mystery novels -- actual mysteries, in which no one knows whodunnit yet, though a whole lot of people have theories. Things that are hard to think about, or crazy difficult to conceptualize. The nature of space-time. Infinity. Perception. (My favorite my favorite exhibit at the Exploratorium in San Francisco was always the optical illusions.)

First, it was books like Richard Wolfson's Relativity Demystified, Brian Greene's The Elegant Universe, Michio Kaku's Parallel Worlds, Mario Livio's The Golden Ratio. All the grand mysteries of the universe, its structure, and the math and physics underlying it. I didn't completely grasp the details of the theories, but it was sure fun to try!

Then I decided to read about people. I honestly don't remember why I picked up Susan Blackmore's Consciousness: An Introduction -- was I just browsing the generic non-fiction science books section? I remember the library. I remember kneeling on the carpet, pulling the book off one of the lower shelves.

This book opened my eyes.

At first, I was a little disappointed. Why couldn't Susan tell me how people worked? How I worked? I wanted answers! How am I a person? Why am I a person? Why can I think about myself thinking? Perhaps I'd assumed, up until that point, that scientists had all the hard problems figured out and now were just filling in the details.

My dismay was swiftly and thoroughly overridden by the realization that here was one of the Big Questions in the universe. Still so much left to discover. The twinkling thought: could I help discover it? And utter fascination. I distinctly remember standing on the local community college campus before a class, staring wonderingly at the landscaping, thinking, what is it like to be a tree?

So I read more. I read what I could find in my local public library system. (I wonder what I would have read and learned had I instead had a proper university library at my fingertips.) I also bought a copy of Douglas Hofstadter's Godel, Escher, Bach, which intrigued and confused me. I was severely disappointed by Andrea Rock's The Mind at Night, because I'd naively assumed that I could read one book and then understand why people sleep and how dreaming works.

I read William Calvin's How Brains Think, which didn't actually tell me how brains think but did introduce me to some relevant terminology. I learned how complicated memory is and how to pronounce aplesia from Eric Kandel's memoir In Search Of Memory. Judith Rich Harris's No Two Alike was part of my introduction to the nature-nurture debates, a lot of twin studies, and just how important the environment and an organism's interactions with it are in determining what the organism is like.

I read Malcolm Gladwell's Blink, Stanislas Dehaene's The Number Sense, and some others, too. As before, I'm quite sure that I did not fully understand any of the theories presented, not having a background in cognitive science, psychology, philosophy, or neuroscience at that point.

Basically, I discovered the mind sciences at an opportune moment, in time to sign up for an introductory cognitive science course my freshman year.

And now?

I still don't know why or how I'm a self-aware person. No one does. I do, however, have a much better idea of the theories other folks have, the problems being tackled, and some of the methodologies being used in the quest. Maybe, now, I'll be able to help solve the mystery myself.